Avian Pox

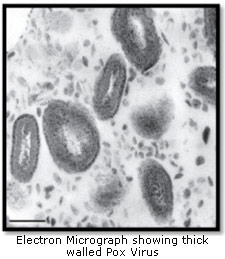

Avian Pox is a relatively new (and emerging) disease in the UK, which seems to be increasingly identified in garden birds. The disease is caused by an AviPox virus - a thick walled virus. The virus causes two types of disease – a dry ‘cutaneous’ (skin) form which stimulates excessive skin growth and nodular warty lesions. This type of pox infection is most commonly seen in our garden birds. The other ‘wet’ form of the disease, is more commonly seen in domestic chickens and turkeys, where the virus infects the mucous membranes of the digestive and respiratory tracts. This electron micrograph of a pox virus, shows how thick walled the virus is. This thick wall enables pox viruses to be extremely resistant to environmental factors (such as disinfectants), and the virus survives and multiplies really well in dry conditions. This is why Pox lesions are seen more commonly in the summer months than the winter.

It would seem that currently Great Tits are more predisposed to Avian Pox infection than other UK garden birds however lesions have been recognised in Dunnocks, Wood Pigeons, Blue Tits, and I have also seen Blackbirds with Pox lesions.

In most other species, the virus will cause mild lesions, usually on the featherless areas - the legs and around the eyes and beak. Often seen as bald/scaly patches, or pinky/grey plaques, these birds often mount an immune response to the virus and survive the infection.

However in Great Tits, extensive wart-like nodules can develop, which can then impede their ability to fly, feed, breathe or even to see. If these birds can continue to feed, it is possible for them to recover, and they are left with only minor scars. In severe cases, the birds may not survive.

The virus seems to invade the bird via abraded skin and mucous membranes- either from infected perches and feeding stations or possibly through biting flies, which again, are more common in the summer months.

Because it is a relatively resistant virus, (due to its protective wall) it can survive on contaminated perches and feeding stations (particularly in dry summer months) for a considerable time – infecting a number of birds in one garden.

Avian Pox virus does not seem to be infectious to humans, however if you have to handle infected birds, do make sure you wear gloves and follow the hygiene measures which I have written about.

Whilst the larger, more prominent Pox lesions are distinct, it may be worth remembering that smaller, less obvious lesions may be other things such as injury scars or tick infestations, as can be seen in this accompanying photo of a Reed Warbler infected with a tick. The tick will fill with blood and drop off spontaneously.

Because this disease seems to be spreading within UK garden birds, there are a number of groups studying the incidence of cases and the spread of the disease. If you do find Pox infected birds in your garden, please call RSPB Wildlife Enquiries on 01767 693690 and help them to track what is happening in the UK.

And one last request from me........ if you do see infected birds (with Pox virus or any other disease/malaise), I would be really grateful if you could take photographs and send them to me. I will use them to put together a library for my vet pages, and for each photo I use, I will send a £5 gift voucher to spend with us.

With sincere thanks to Liz Cutting for the use of her photographs. www.lizcuttingphotos.com

Trichomoniasis

Like Avian Pox, Trichomoniasis is a relatively new and emerging disease affecting British Garden Birds.

However unlike Avian Pox virus infection, garden birds which become infected with the Protozoal parasite (called Trichomonas gallinae ) will not usually survive. The parasite survives in moist conditions, needs water to survive and will be killed by dessication.

A photomicrograph of two Trichomonas protozoa parasites can be seen here.

Trichomoniasis, (or ‘Canker’ as the disease is also known), was a significant problem for pigeons and doves in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s. A school boyfriend of mine (many years ago now!), had racing pigeons that suffered an outbreak of Canker which had a dramatic effect on their health. The pigeons suffered with nasty necrotic (cheesy) ingluvitis- which is an inflammation of the crop and oesophagus.

Fortunately, effective in-water antibiotics were quickly developed in response to this new disease, and nowadays it is less commonly diagnosed. However it is still seen in Game birds and Poultry.

For some unknown reason the parasite then jumped host group to have a dramatic effect on the UK wild finch population. Although Greenfinches are most frequently affected by T. gallinae infection in garden environments (and Chaffinches somewhat less so), the reasons for this are not clear.

The Greenfinch is one of the species most frequently affected by other infectious diseases that are commonly diagnosed in garden birds, such as Salmonellosis and Colibacillosis (Lawson and Cunningham, unpublished data). It may be that the gregarious and seed-eating habits of finches, sharing food and water at feeding stations, with high contact rates, are likely to facilitate pathogen spread. Trichomoniasis, however, is confirmed much less frequently in other sociable and flocking garden birds ,so feeding behaviour is unlikely to be the sole driver of Greenfinch susceptibility.

The disease was first recorded in a British finch in April 2005. Small numbers of dead finches were reported throughout 2005, but then the disease exploded in 2006 and 2007 as infection spread and the British public reported their findings;

fluffed up, lethargic finches (mainly Green finches and Chaffinches, but also a few Collared doves and wood pigeon also succumbed to the parasite, and at that time, the only other species in which the condition was diagnosed were House Sparrows (9 cases), Yellowhammers (4 cases),

Dunnocks ( 3 cases) and Great Tits ( 2 cases )

Prior to this epidemic of Trichomoniasis, low levels of finch mortality due to Salmonellosis were recorded annually, with the peak occurring during the months of December and January, however this new disease significantly increased mortality and in some areas 35% of Greenfinches and 21% Chaffinches died. When you consider that there are approx. 4million Greenfinches in gardens in the UK, the total number of deaths was huge.

The inability to swallow causes excessive saliva to build up and birds have wet facial and chest plumage. Many also have difficulty breathing and are emaciated.

Laboratory examination of these dead birds usually shows a necrotic mucosal ulceration of the crop and oesophagus area. The photograph on the right hand side is unpleasant to look at but it does highlight just how significant the pathology is when these birds become infected. No wonder they cannot swallow- poor things.

Although we have quantified the occurrence of Trichomonas gallinae in dead birds, the overall prevalence ( i.e how many birds in the UK are infected) remains unknown. Prospective studies to screen multiple species of live birds for the parasite would help address this knowledge gap- but this is unlikely ever to be possible.

The Trichomonas gallinae parasite survives and thrives in still moist conditions (such as bird baths, wet bird tables) and will be destroyed by dessication ( drying out).

It lives in the upper digestive tract and therefore the most likely way that it is spread between birds is via saliva. This can be direct spread during courtship and when infected adults feed their young, and indirectly, via saliva-contaminated water and food.

If you see diseased finches or find a dead bird in the garden, my advice would be to stop feeding for at least 14 days and preferably 21 days. Bird baths should be emptied, scrubbed and left dry. Similarly with bird feeders, tables etc. People worry about stopping feeding, but if dirty bird baths and feeders are allowing the parasite to continually infect healthy garden birds, then the disease will continue to circulate.

Please see my section on health and hygiene for more specific control measures.

Salmonellosis

Salmonella species are rod-shaped bacteria which are zoonotic. That means that they can spread from animals or birds to infect humans. There are approximately 2,000 strains of Salmonella spp in existence, and humans, domestic and wild animals, and domestic and wild birds can all become infected with certain strains of Salmonella spp. Not all strains can infect all species, but there are Salmonella strains which can be transferred from one species to another and cause disease in both. It is all quite complicated!

The most commonly isolated stains of Salmonella in wild birds in the UK (identified as a result of the submission of dead birds to UK Veterinary laboratories) are those of Salmonella Typhimurium, strains DT40, DT56 and DT160. A large scale study of garden bird mortality which was conducted in England and Wales between 1993 and 2003 (before Trichononiasis was recognised), identified Salmonella Typhimurium as the main pathogen isolated, and the majority of deaths due to Salmonella occurred during the winter months.

Flocking birds such as Greenfinches, Chaffinches and House Sparrows seemed to be most commonly affected, and interestingly, male Greenfinches were much more frequently diagnosed with Salmonellosis than female ones!

The Salmonella organisms invade the digestive tract of wild birds.

They can cause ulceration of the crop and oesophagus and severe inflammation of the intestines – leading to diarrhoea. The bacteria are present in large numbers in infected droppings and these are the source of contamination for uninfected birds. Infected birds will look puffed up and often will just sit on the ground or on feeding perches – failing to respond to danger. Interestingly, birds will often continue to eat, despite being severely ill. Obviously the risk of transmission is greatest where large numbers of birds gather at communal roosts or feeding sites, and poor hygiene at feeding stations can facilitate an outbreak.

While most infected birds die, some do not show any symptoms and can act as carriers. Salmonella bacteria are fairly hardy and can survive in the environment for some time.

This path photo shows a Siskin which died of Salmonella typhimurium D56. It was one of 30 birds which died in a single garden over a 30 day period. You can see really nasty and extensive necrotic ulcers in the crop. Other birds had severe haemorrhagic enteritis. Because droppings are the source of infection, the best way therefore to prevent an outbreak of Salmonella is to prevent faecal contamination of the water and food being offered.

Because there is a real zoonotic risk with Salmonella typhimurium it is very important to take care to exercise good personal hygiene when cleaning feeders and water containers and when handling sick or dead birds it is imperative that you wear disposable gloves, and ensure thorough washing of hands and arms. Prevention is always better than cure and following 'Best Practice' feeding guidelines will help you prevent disease occurrence in your garden.

The guidelines are the same for any organism under consideration;

Ensure good feeding hygiene - clean and disinfect feeders and clear up uneaten food and droppings

Provide clean drinking water and clean bird baths on a daily basis

Move feeding stations and split your daily offering into a number of separate feeding areas to reduce contamination build up

Offer high quality food and don’t over-supply food- feed to demand.

If you have photographs of diseased garden birds, which you have taken yourself, and you would like to send me, please get in touch. I will use them to put together a library for my vet pages, and for each photo I use, I will send a £5 gift voucher to spend with us.

Many thanks!

Lesley

Back

Back Bird Feeders

Bird Feeders  Seed Feeders

Seed Feeders Peanut Feeders

Peanut Feeders Peanut Butter Feeders

Peanut Butter Feeders Suet & Fat Feeders

Suet & Fat Feeders Window Feeders

Window Feeders Hanging Feeders

Hanging Feeders Feeding Stations

Feeding Stations Ground Feeders

Ground Feeders Easy Clean Feeders

Easy Clean Feeders Bird Tables

Bird Tables Seed Trays

Seed Trays Bird Baths & Drinkers

Bird Baths & Drinkers Feeder Accessories

Feeder Accessories Feeder Hygiene

Feeder Hygiene Squirrel Proof Bird Feeders

Squirrel Proof Bird Feeders For the Kids

For the Kids Niger Seed Feeders

Niger Seed Feeders Mealworm Feeders

Mealworm Feeders Bird Food Storage

Bird Food Storage Fat Ball Feeders

Fat Ball Feeders Tube Feeders

Tube Feeders

Our Farm

Our Farm Contact Us